Schubert Sonatinas & Rondo - Electronic

CHRCD080-E

- About

Artist(s):

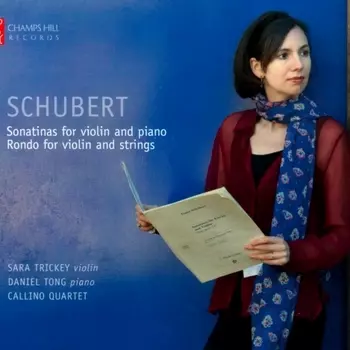

Sara Trickey brings her "beautifully refined tone" (Musical Opinion) and her "fiery and passionate performance style" (The Strad) to Champs Hill Records with an album of early Schubert works for violin.

Composed in 1816 (Schubert was 19 and already the composer of such landmark Lieder as 'Gretchen am Spinnrade' and 'Der Erlk'nig' as well as several symphonies) this collection of sonatas were originally published as 'Sonatinas' aimed at the lucrative amateur music market in 1836, eight years after Schubert's death.

However the Sonatas in D major (D384), A minor (D385) and G minor (D408) are musically more ambitious than their titles might suggest, as Sara Trickey explains:

"I see in them all the ingredients of Schubert's voice - the joy mixed with frailty, the poignancy and darkness which never quite subsumes a sense of hope - but mapped out on a slightly less epic canvas than many later and more famous works. There are passing hints of almost everything that is to come, but they are presented innocently here, in a way that is sometimes mistaken for triviality. I wanted the sonatinas to hold centre stage on this disc, rather than being seen just as precursors to the wonderfully rich Fantasy and Grand Duo sonata which were written later for the same combination of instruments."

Sara is joined by Daniel Tong at the piano for the Sonatinas and by the Callino String Quartet for the Rondo for violin and strings in A major, D438

- Sleeve Notes

When thought at all as an instrumental player, Franz Schubert tends to be remembered as a pianist, most often accompanying one of his own songs (having himself effectively created the German art song or Lied). However, as a budding composer in his teens he distinguished himself particularly as a violinist. Schubert received his first violin lessons at the age of eight from his father, Franz Theodor Schubert, a school teacher who ran his own primary school in Vienna. In the opening decade of the 19th century, an Austrian schoolmaster in such a position was expected to be able to teach music; so it was that the future composer received his first elementary lessons from his father, while receiving his first piano lessons from his elder brother, Ignaz, who also taught at their father's school.

By the age of seven, Schubert's musical ability was such that he was sent to the local choirmaster, Michael Holzer, to study singing, organ playing and counterpoint. However, such was Schubert's ability ' as his brother Ferdinand recalled ' that Holzer confessed with tears in his eyes that 'whenever I wanted to teach him anything new, he already knew it. I often simply stared at him in silent astonishment.' According to Schubert's father, the result was Holzer did not so much give lessons as 'simply whiled away the time with him'.

Schubert had, in the meantime, been introduced to Antonio Salieri, the composer whose reputation has since been much maligned by the rumour (first widely propagated by the Russian writer Alexander Pushkin) that he machinated and even poisoned his rival Mozart. Salieri, by then Vienna's Court Music Director, was so impressed with Schubert's musicianship and, crucially, his singing that he arranged for Schubert to audition for the imperial Hofkapelle. Passing his audition, Schubert in effect became a choral scholar at the Kaiserlich-k'nigliches Stadtkonvikt (Imperial and Royal City College), Vienna's principal boarding school for non- aristocrats, so gaining the best possible education he could receive given his humble middle-class background. Schubert's violin playing sufficiently impressed

his teacher there, Ferdinand Hofmann, who noted that his student 'plays difficult pieces at first sight'. Schubert also played violin in the school orchestra, whose repertoire included Haydn, Mozart, early Beethoven and their lesser Viennese contemporaries.

Schubert also regularly played viola in the family string quartet, as well as in a small orchestra that performed regularly at the houses of the Viennese merchant Franz Frischling and, from early 1816, the violinist Otto Hatwig. So by the time Schubert came to compose the first three of his violin sonatas in 1816 he was thoroughly familiar with the technique and idiosyncrasies of violin playing. By then just 19, Schubert was yet already the composer of such landmark Lieder as 'Gretchen am Spinnrade' and 'Der Erlk'nig' as well as several symphonies and at least three Masses.

Those first three violin sonatas ' composed in March and April of 1816 and originally titled by Schubert 'Sonatas for piano, with violin accompaniment' ' were subsequently re-christened Sonatinas by Diabelli when published in 1836 (eight years after Schubert's death), no doubt with the hope of catching the lucrative amateur market. Given the sheer prodigious volume of works Schubert created in his lifetime, it is perhaps not surprising that for a long time musicians and scholars took Diabelli at his word and assumed that those three sonatas were as modest in their ambition as their published title suggested. Indeed, the most frequently performed of the three ' that in D major ' appears quite modest in its technical demands. Yet even this sonata contains some of Schubert's most characteristic and lovely melodies, and a finale with a theme that has more than a passing resemblance to that of the scherzo of his Trout Quintet, composed some three years later. Also characteristic of Schubert are the surprising and far-ranging modulations of its first movement, cast in a conventional sonata form. The second movement Andante, after an opening of Mozartian grace, presents one of Schubert's loveliest melancholic melodies.

One may also hear reminiscences in all three sonatas of works by other leading composers of the day ' Beethoven, and especially Mozart, whose music Schubert loved above all others. Schubert confessed at the end of his life that Mozart's Symphony No. 40 in G minor in particular had impressed him when he played it in the school orchestra, and its shadow is strongly felt in the second of his violin sonatas, that in A minor, also the most adventurous of the three works. Yet at the same time Schubert transmutes this influence and the music in this Sonata in particular appears to look forward to composers of future generations.

The A minor's opening sonata-form movement presents not just two but three different musical subjects, each in its own key (a practice Schubert would repeat in such mature works as his String Quintet and the B flat Piano Sonata): first, after a deceptively gentle introduction by the piano, a Sturm und Drang angular theme by the violinist accompanied by pounding chords; then a more songful second subject, typical of Schubert (though, when later chromatically enriched during its development, sounding almost like Borodin!), followed by a lighter third subject which seems to anticipate Mendelssohn. The second movement, opening with a lovely and noble chorale-like theme (which has a passing resemblance to the opening theme of the finale of Mozart's Violin Sonata K377), is perhaps the closest Schubert comes to Beethoven in style, yet again surpassing even the German master in the richness of its texture and its expressiveness which appear to anticipate Brahms. Mozart's G minor Symphony is most clearly the model for the third movement minuet and trio, as it was for Schubert's almost contemporary Fifth Symphony: like the Symphony's equivalent movement, this has a brusque minuet, and a beguiling trio section as contrast. The rondo finale opens with a rather wan violin theme, but soon enters more dramatic territory of almost Beethovenian ferociousness.

The Third Sonata opens with a severe dotted-rhythm theme played in unison, sounding more like an anticipation of Schumann than a recollection of Beethoven or even Mozart. Again, as in the A minor Sonata, the opening movement's exposition ' in the course of which the severe opening idea is reworked and transformed ' embraces three rather than two main key centres. Balm is offered by the slow, song-like second movement of Mozartian calm, followed by a Minuet whose trio section has a strong resemblance to that of Mozart's Symphony No. 39. The finale starts in reflective Schumann-like vein, but soon brightens into a light- hearted and almost throw-away style.

Schubert's Rondo for Violin and String Orchestra was composed in June 1816, the same year as the three violin sonatas, though it was not published until 1897. Again, it reflects Schubert's admiration for Mozart, yet is quite different in character. For whom or what occasion the A major Rondo was composed for remains something of a mystery, though Otto Hatwig, who hosted and led the orchestra Schubert played in may have been the intended soloist. Until Schubert composed his violin showpieces of 1826 and 1827 ' respectively the B minor Rondo and the C major Fantasy ' the A major Rondo was easily the most challenging work he composed for solo violinist. It opens with a gracious Adagio, in which after a brief introduction the soloist unfurls and ecstatically sings before embarking in a light-hearted rondo very much in the style of a Mozart finale.

Daniel Jaffé

- Press Reviews

" ... an outstanding recital..."

" Trickey has a beautiful tone; it's sweet, clear and pure. . . Tong is an equal partner in every respect." " . . . a simply stunning CD."

- The Whole Note"These are first-rate players [Trickey & Tong], and these readings are delightful and satisfying."

- American Record Guide- Delivery & Returns

If you order an electronic download, your download will appear within your ‘My Account’ area when you log in to the Champs Hill Records website.

If you order a physical CD, this will be dispatched to you within 2-5 days by Royal Mail First Class delivery, free worldwide.

(We are happy to accept returns of physical CDs, if the product is returned as delivered within 14 days).

If you have any questions about delivery or would like to notify us of a return, please get in touch with us here.