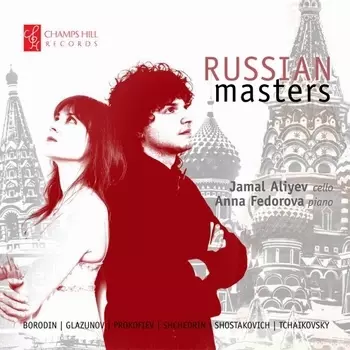

Russian Masters - Electronic

CHRCD127-E

- About

Artist(s):

Borodin - Glazunov - Prokofiev - Shchedrin - Shostakovich - Tchaikovsky

When Jamal Aliyev and Anna Fedorova first had the joy of playing together in the Prussia Cove musicians' seminar, their musical spark was immediately apparent. Subsequently, they have played together numerous times. Their unique and sensitive form of music making has stolen the hearts of countless music lovers.

In 2014, they were invited to Champs Hill to give a recital in which they showcased their strength in the Russian romantic era classics. Following discussions with David and Mary Bowerman on the wonderful opportunity to record for Champs Hill Records, Anna and Jamal had no doubt that a disc of Russian repertoire would represent them both most successfully. Jamal writes in his introduction to the CD:

"Although my parents grew up in different environments - my mother is of Jewish descent and my father Armenian/Azerbaijani of Christian and Muslim origin - they were both schooled in the Soviet music system.

It is because of this history that I find it incredibly natural to have such love for works by Russian composers.

Being given the exciting opportunity to record these masterpieces for Champs Hill Records has brought me one step closer on the limitless path of comprehending the message of these composers.

- Sleeve Notes

When Prokofiev heard the 20-year-old Rostropovich perform his Cello Concerto in 1947, he was inspired to compose a sonata for him. This late period of Prokofiev’s life is rather cello-orientated. As well as re-working the concerto with Rostropovich’s assistance, he worked on a concertino and a solo cello sonata, both left unfinished. It was Rostropovich’s phenomenal artistry which helped to keep Prokofiev’s inspiration alight at a most difficult time for Soviet composers. In common with many other 20th-century Russians, Prokofiev had chosen exile, but he subsequently – and surprisingly – returned, resettling in Moscow in 1936. Twelve years later he and other composers suffered official criticism in the notorious Zhdanov Decree, but in answer to this humiliation he produced an affirmative, attractively diatonic cello sonata, completed in the spring of 1949. In keeping with the authorities’ demand for more accessible music, Prokofiev composed a sonata of especially direct and cloudless character, almost entirely free from the subversive or abrasive elements common to many of his earlier works.

At the head of the manuscript of the Cello Sonata Prokofiev wrote “Man! The word has such a proud sound!” – a quotation from Maxim Gorky’s play The Lower Depths, aptly reflected in the noble bearing of the opening theme. At the recapitulation this melody becomes even more dignified in its sonorous octave doubling. This opening movement is blessed with a prodigal amount of memorable material, remarkable even for such a phenomenally gifted melodist as Prokofiev. A contrasting rhythmic idea is introduced by the cello (Moderato animato) and the coda has some hyperactive passage-work, but the over-riding impression is of radiant eloquence and simplicity. The poetic ending includes the imaginative effect of tremolo-like oscillation between two harmonics.

The central movement is predominantly playful and childlike, lacking the malicious or sardonic undercurrents of many Prokofiev scherzos, and has a contrasting middle section (Andante dolce) based on a generously expressive melody characterised by wide intervals. This is Prokofiev at his most endearing. The principal melody of the sonata-rondo finale, again with many wide intervals, establishes a genial tone, but here, as in the opening movement, the composer’s fondness for unprepared shifts of key adds piquancy. One episode, marked Andantino, introduces a more intimate mood amidst the prevailing high spirits, and the coda recalls the very opening theme of the sonata in grandiose manner. Seriously ill in hospital, Prokofiev was unable to attend the premiere, given by Rostropovich and Sviatoslav Richter on 1st March 1950.

Shostakovich began his Cello Sonata in mid-August 1934 and completed it within a few weeks. At that time he cultivated a style of greater simplicity and before he had even begun the sonata he expressed his intention to compose a work in classical style. The piece was commissioned by Viktor Kubatsky, principal cello of the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra, founder of the Stradivarius Quartet and recital partner of the composer. Having fallen in love with Yelena Konstantinovskaya, a 20-year-old translator, Shostakovich separated from his wife Nina. Divorce papers were prepared, but husband and wife were reunited the following year. The sonata-form opening movement begins with a lyrical though latterly rather restless melody which soon develops into a more strenuous passage with triplet figuration, eventually arriving at a fortissimo climax. A second theme, molto espressivo in B major, is introduced by the cello. The development section is dominated by an idea which Shostakovich has introduced at the very end of the exposition – an enigmatic, potentially subversive element in low octaves and of distinctive staccato rhythm. In the final section of the movement, marked Largo, the cello recalls the first theme above a stalking piano accompaniment in clipped quavers, before the subversive element has the last word deep in bass.

The much shorter second movement is a heavily accented scherzo of rugged humour and with an abundance of material. Scintillating groups of arpeggios played by the cello in glissando harmonics are the most striking incidental feature. The ending is dismissive. Bleak and sombre in character, the Largo is akin to the final act of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the opera which was denounced by the Soviet authorities after its premiere in January 1934. The cello introduces both main themes, the first muted, while the piano plays an accompanying role almost throughout, its only sustained melodic passage being a recall of the noble second theme at a much higher pitch than originally. At times reminiscent of the burlesque parts of the Concerto for piano, trumpet and strings (1933), the rondo-finale is characterised by sardonic humour, in extreme contrast with the Largo. In the first episode the cello’s manic passage-work in 6/8 is pitted against 2/4 in the piano. Later the piano has a long section of even more frenetic semiquavers, before the cello continues the momentum in the background against the second reprise of the opening theme. In the coda the legato line of the piano is accompanied by the cello’s strumming, and again the ending is perfunctory. Both this relatively early work and Prokofiev’s late sonata are among the landmark cello works of the 20th century.

Tchaikovsky’s publisher Pyotr Jurgenson commissioned the 6 Morceaux for piano, Opus 19 in 1873. The Nocturne in D minor, the fourth piece, is marked Andante sentimentale and is based on the kind of memorable theme which came naturally to Tchaikovsky, irrespective of whether he was occupied with symphonies or with works of lesser stature. Its middle section (Più mosso, in 3/4) is followed by the return of the opening melody, now with a graceful new accompaniment. Tchaikovsky himself made an arrangement for cello and orchestra in 1888, but this cello and piano version was arranged (and transposed from C sharp minor into D minor) by Wilhelm Fitzenhagen, the cellist for whom Tchaikovsky would compose his Variations on a Rococo theme. The soloist in the premiere of the cello version of the Nocturne was Anatoly Brandukov, for whom Tchaikovsky also wrote the Pezzo capriccioso in B minor in 1887. Following the arresting introduction, the main theme is a stepwise ascending melody (molto cantabile e grazioso) of typically unaffected charm. The “capriccioso” of the title reflects not only the demisemiquaver figuration in the alternating episodes, but also the rhapsodic tendencies of the cello part, as it takes wing with groups of triplets in the principal sections. No less unpredictably, this delightful piece does not finally return to the opening melody, but ends with the brilliant figuration, crescendoing to fortissimo, and an abrupt cadence.

Glazunov’s Chant du Ménestrel (Minstrel’s Song) dates from 1900 and was originally scored for cello and orchestra. A brief introduction leads to an eloquent melody in F sharp minor, marked dolce ed appassionato. After a Poco più mosso middle section in D major – less soulful, more genial - the original theme returns, now with melody and accompaniment roles reversed.

Borodin worked on Prince Igor intermittently for nearly twenty years. Still unfinished at his death, the opera was completed by Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazounov. The story is based on a twelfth-century epic telling of the struggle between Prince Igor, leader of the Russians (who are Christian), and the Polovtsi, a pagan and nomadic eastern tribe. Igor is captured but escapes with the help of Ovlur, a Polovtsian soldier who has converted to Christianity. The Polovtsian Dances constitute the finale of Act Two, as sensuous slave-girls perform for Igor’s entertainment. This exhilarating sequence displays Borodin’s beguiling melodic gift as well as the harsh, fantastic and barbaric qualities which are equally characteristic of the opera in general. Prince Igor was premiered in St. Petersburg on 23 October, 1890. This version for cello and piano has been arranged by the cellist Jamal Aliyev.

Shchedrin’s In the Style of Albéniz dates from 1952 when he was still a student at the Moscow Conservatoire. Shchedrin originally composed the piece for solo piano but alternative versions include his own 1995 arrangement for cello and piano and several transcriptions by other hands. Pungently Spanish in character, it also has a strong flavour of caricature, with halting rhythms and extravagant, flamenco-like gestures. The result is much more volatile than any music Albéniz himself ever composed. Shchedrin dedicated the piece to his future wife, the famous prima ballerina assoluta Maya Plisetskaya (1925–2015). He later arranged two Albéniz tangos for her.

© Philip Borg-Wheeler

- Press Reviews

- Delivery & Returns

If you order an electronic download, your download will appear within your ‘My Account’ area when you log in to the Champs Hill Records website.

If you order a physical CD, this will be dispatched to you within 2-5 days by Royal Mail First Class delivery, free worldwide.

(We are happy to accept returns of physical CDs, if the product is returned as delivered within 14 days).

If you have any questions about delivery or would like to notify us of a return, please get in touch with us here.