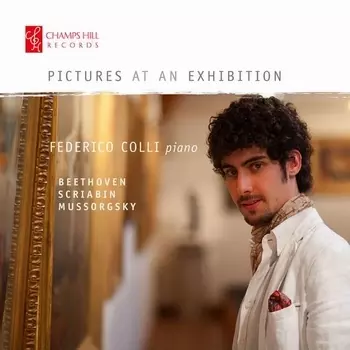

Pictures At An Exhibition - Electronic

CHRCD079-E

- About

Artist(s):

Champs Hill Records is delighted to release the debut recording by winner of the Leeds International Piano Competition 2012: Federico Colli. It will be released in advance of his debut in the International Piano Series at London's Southbank Centre on 22 April, 2014. He will also feature on the cover of Pianist magazine.

"Thank you from the bottom of my heart for giving that wonderful memorable recital in Leeds. You were a great success and a great sensation from every point of view. Your playing was magisterial and you have the flair for communicating with your audience because you have charisma." (Dame Fanny Waterman - University of Leeds Concert Hall, April 14th 2013).

Born in 1988, Federico studied in Milan and Salzburg under the guidance of Sergio Marengo.

- Sleeve Notes

Scriabin and Mussorgsky may seem odd company for Beethoven. Yet Beethoven was the first major composer to introduce Russian music to continental Europe when in 1806 he took Russian folk themes from the collection by Nikolai Lvov and Johann Pr'c, using them in two of his Razumovsky String Quartets, Op. 59. Russia reciprocated, staging the first complete performance of Beethoven's Missa solemnis in 1824 and revering him ever afterwards. Balakirev taught his own band of talented amateurs, the 'mighty handful' of which Mussorgsky was a member, to study Beethoven's symphonies: Mussorgsky's early B flat Scherzo for orchestra is clearly modelled after the Scherzo in Beethoven's Fourth. During the Soviet years, Beethoven's reputation became even more unassailable as Lenin became known as a great admirer, writing of the Beethoven Sonata programmed by Federico Colli on this album: 'I know nothing that is greater than the Appassionata; I would like to listen to it every day. It is marvellous, superhuman music. I always think with pride ' perhaps it is na've of me ' what marvellous things humans can do.'

Beethoven composed this ferociously impressive Piano Sonata in F minor, Op. 57, in the summer of 1804, the year after he had completed the Eroica Symphony. In that summer he had enjoyed what he described as a 'lazy' period in the spa town of Baden, which clearly refreshed him as he almost immediately afterwards composed the F minor Sonata, together with the Piano Sonata in F major, Op. 54, while staying in the village of D'bling just north of Vienna. Beethoven's pupil, Ferdinand Ries, recalled that Beethoven's compositional process involved long works in the nearby Vienna Woods: 'We went so far astray that we did not get back to D'bling until nearly 8 o'clock. He had been humming, and more often howling, always up and down, without singing any definite notes. When questioned as to what it was, he answered, 'A theme for the last movement of the sonata [Op. 57] has occurred to me.' When we entered the room he ran to the pianoforte without taking off his hat. I sat down in the corner and he soon forgot all about me. He stormed for at least an hour with the beautiful finale of the sonata. Finally he got up, was surprised that I was still there and said, 'I cannot give you a lesson today, I must do some work'.'

The Sonata in F minor, Op. 57, eventually gained its name Appassionata when a piano duet arrangement was published and so-christened by the Hamburg publisher Cranz in 1838. As this was 11 years after Beethoven's death, the claim sometimes made that Beethoven approved the title may appear moot; yet there exists an autograph copy of the Sonata subtitled 'La Passionata'. In any case, the name has been widely thought apt as it is one of Beethoven's stormiest creations. Indeed, its sudden fortissimo outbursts, as may be heard even in the first page of the Sonata, and its ferocious passagework would have been unthinkable on the Walter fortepiano Beethoven owned before 1803; in that year, he was presented by the Parisian firm Erard with a forte- piano en forme de clavecin, a more powerful and sturdier instrument which assigned three strings per note and used the action originally developed for the English square piano. The Appassionata's tempestuous nature would impress several composers of the following generations, notably influencing such F minor works as Schubert's Piano Sonata D625, and Mendelssohn's final String Quartet Op. 80.

The Appassionata's first movement has a brooding opening, tense as if before an imminent storm; this soon bursts, with tremolandos and arpeggios cascading over the length of the keyboard. A second melodic theme of noble character appears, but is soon swept away by the opening ideas as they are further developed, only to eventually re-emerge in the recapitulation before a final impassioned coda. The following Andante movement, a set of variations on a chorale-like theme, is like the calm at the eye of the storm, which resumes in the Allegro finale which follows without a break.

Nature, albeit of a sunnier kind, also inspired Scriabin. His final Piano Sonata, No. 10 Op. 70, was composed in the late summer of 1913 in the country estate of Petrovskoye, Kaluzhskaya Oblast. Scriabin's musical language had by then evolved well beyond the Chopin-style melodiousness with which it had so masterfully started, Scriabin having invented a richly chromatic language which explored harmonic territory similar to but quite independent of Schoenberg's so-called atonal works and Debussy's more adventurous piano works. Scriabin himself described his Tenth Sonata as 'bright, joyful, earthly' and spoke of 'the impression of a great forest' that had inspired it. Certainly the work opens in an atmosphere of mystery ' introducing the main elements of an augmented triad followed by a diminished triad, their alternation suggesting the very breathing of the music, and a chromatic line ' before launching, with a series of trills, the main allegro section. These ecstatic trills which fill the music have often been associated with the buzzing of insects: the composer himself described the work as a 'Sonata of insects... born from the sun; they are the sun's kisses.' Elsewhere, though, Scriabin described such trills as may be heard in his earlier late period sonatas as 'palpitations... vibrations from the universe', which suggests that his emphasis was on the benevolent influence of the sun rather than insects themselves. Indeed, it is a sun- filled, ecstatic world already well-mapped in his earlier works of that period, and which Stravinsky, then a great admirer of Scriabin's, promoted to a wider audience in depicting the title character of his first ballet The Firebird. Ultimately Scriabin's music was not intended to be 'of this world', but shared with the Symbolist poets of his time the aspiration of transcending mortal existence through the revelation of art, through which one might discover the essence of being rather than its mere substance.

Of quite a different persuasion was an earlier revolutionary composer, Mussorgsky, who in the late nineteenth century aspired to create music that truly reflected the grit and individuality of human existence. Complementing this was his fascination with Russian folklore and the world of imagination, most particularly that of a child, as exemplified by the first song of his cycle The Nursery, 'With Nanny', in which a child begs his nyanyushka to tell his favourite tales. It was this world particularly which was evoked by the artist, Viktor Hartmann, whose drawings and elaborate architectural designs reflected his preoccupation with peasant artwork and folklore, often involving elaborate filigree with suggestions of birds, snakes and fantastical creatures. It was in Hartmann's memory that Mussorgsky composed his now most famous work, Pictures at an Exhibition.

The immediate spur to this was an exhibition of Hartmann's drawing, designs and paintings organized after the artist's death, aged 39, in 1873. That Hartmann also shared something of Mussorgsky's interest in closely observing ordinary life is evident from an article about the pictures by the exhibition's organizer, Vladimir Stasov: 'One-half of these drawings shows nothing typical of an architect [but depicts] scenes, characters and figures out of everyday life, captured in the middle of everything going on around them: on streets, and in churches, in Parisian catacombs and Polish monasteries, in Roman alleys and in villages around Limoges.' Stasov went on to list some of the characters portrayed by Hartmann: 'workers in smocks, priests with umbrellas under their arms riding mules, elderly French women at prayer, Jews smiling from under their skull caps, Parisian rag-pickers...'

Already the composer of the mighty opera Boris Godunov, Mussorgsky found Pictures at an Exhibition a welcome break from the labour of composing concurrently his two subsequent operas, Sorochintsy Fair and Khovanshchina. Even so, he scarcely treated Pictures as a throw-away project: 'Hartmann is boiling as Boris boiled;' he wrote to Stasov, 'sounds and ideas have been hanging in the air; I am devouring them and stuffing myself ' I barely have time to scribble them on paper.'

Just six (out of a possible ten or eleven) of Hartmann's original pictures depicted in Mussorgsky's cycle have been discovered. Charming as several of those originals are, and for all Stasov's eulogising, they hardly measure up to the powerful piano portraits they inspired. Yet Mussorgsky modestly called the result an 'Album Series'; indeed for a long time even champions of Pictures at an Exhibition ' before Ravel made his successful and repertoire-holding orchestration ' tended to play just selections from the work. In fact, the work is bound into a substantial single entity by several elements, most obviously the opening Promenade, which not only recurs as interludes between several of the 'pictures', but itself becomes increasingly and significantly involved in those depictions. Then, perhaps only felt subconsciously by the listener, there is a key progression starting with B flat major, which ultimately proves to be the dominant preparation for Mussorgsky's final goal: the 'Great Gate of Kiev' in E flat major (incidentally the 'heroic' key of Beethoven's Eroica Symphony!).

The movements of Pictures at an Exhibition are as follows:

I A representation of the gallery's visitor, or perhaps rather his initial impressions as he enters the exhibition: note the fanfare-like motif. Mussorgsky, describing this movement as 'in modo russico', almost certainly had in mind the effect of a precentor answered Orthodox-style by a choir.

II A portrait of a grotesque gnome (Hartmann's design for a nutcracker).

III A gently reflective promenade prepares for...

IV An old castle before which a troubadour is seen serenading.

V A more rumbustious promenade prepares for...

VI Tuileries, the Parisian public garden where children are having a dispute during a (perhaps aborted) game.

VII Without an intervening promenade, we are struck 'right between the eyes' by what Mussorgsky originally called 'The Sandomirsko Bydlo'. A historic town in south-east Poland, Sandomir was ripe in the composer's mind with not altogether positive associations, featuring in Boris Godunov as the town where the pretender plots the protagonist's overthrow. 'Bydlo' is Polish for cattle, though Mussorgsky confided to Stasov that the unnamed element was 'le tél'gue' ' an 'ox cart' ' after which the movement is now generally titled.

VIII A reflective, even brooding Promenade as the visitor ' possibly still mulling over the picture just seen ' unexpectedly comes up against...

IX 'Ballet of unhatched chicks': Hartmann's costumes for children inspire a charming and frankly pictorial piece in which one can hear the cheeping of the baby birds.

X Another sharp contrast. Like 'Tuileries' to 'Bydlo', we are again taken from the world of children back to Sandomir, where Hartmann made several paintings in the Jewish ghetto. A self-important rich Jew refuses to give charity to a poor Jew, whose thin-voiced pleas shiver from the cold.

XI A grand statement of the Promenade theme prepares us for the final sequence.

XII Limoges ' market day: market women gossip loudly in order to be heard above the tumult.

XIII A sudden scene change, casting us into the gloom of the Parisian catacombs, the original picture depicting Hartmann himself with a friend and their guide observing a cage stacked full of skulls.

XIV Then, in one of the work's most haunting masterstrokes, we now hear the promenade theme transformed, played against eerie tremolandos. Still in the catacombs, the viewer is now Mussorgsky himself, according to a pencilled annotation in the score: 'the creative genius of the late Hartmann leads me to the skulls and invokes them; the skulls begin to glow'.

XV Another abrupt scene change as we are brought face-to-face with the ferocious, child-eating witch Baba Yaga. According to Russian folklore, she lives deep in the woods in a hut with hen's legs ' hence the music's clucking sounds.

XVI The final abrupt transition of the work for the final 'picture', inspired by Hartmann's design for a grand entrance to the city of Kiev to celebrate Tsar Alexander II's escape from assassination there in 1866. With interludes representing an Orthodox choir, this reaches a thrilling apotheosis in which the tintinnabulation of bells spells out the promenade theme before the Kiev theme brings the work to a grand conclusion.

Daniel Jaffé

- Press Reviews

"... full of youthful fire ... beautiful shades of colour ... I can almost imagine this is how Beethoven would have played it."

" ... whole release is proof that the Leeds judges made the right decision in selecting Colli as their number one. "

- Pianist Magazine"Colli brings a light, thoughtful touch to the opening of the Allegro assai of Beethoven's Sonata in F minor, Op.57 'Appasionata' contrasting the drama that follows exceptionally well."

"This is a finely paced performance, with Colli, nevertheless, showing a sudden fire in his playing when the music demands it."

"There are moments of beautiful restraint and tension with some lovely delicate playing, Colli showing his fine touch."

"This is a very fine performance that, again, gives a very individual view of [Scriabin's Sonata No. 10, Op.70]. Champs Hill's fine recording allows us to hear all of Colli's superb colouring."

- Bruce Reader, The Classical Reviewer" [Colli] has the most beautiful piano sound: warm, dark, full, and rich."

- American Record Guide- Delivery & Returns

If you order an electronic download, your download will appear within your ‘My Account’ area when you log in to the Champs Hill Records website.

If you order a physical CD, this will be dispatched to you within 2-5 days by Royal Mail First Class delivery, free worldwide.

(We are happy to accept returns of physical CDs, if the product is returned as delivered within 14 days).

If you have any questions about delivery or would like to notify us of a return, please get in touch with us here.