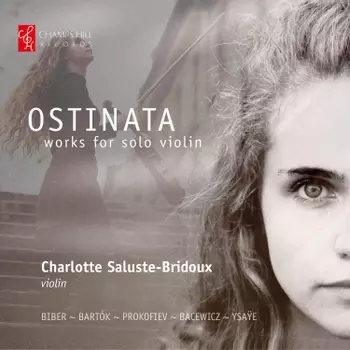

Ostinata - works for solo violin

CHRCD158-E

- About

Charlotte Saluste-Bridoux explores some of the most technically challenging and virtuoso solo violin repertoire for her stunning debut recording. Her programme embraces a mix of the rational and intuitive, of head and heart, in five diverse solo sonatas, each strikingly different in style and substance.

Saluste-Bridoux comments: "This album comprises a collection of violin works that have been at the centre of my musical life for many years. Biber rivals Bartók with his obsessive tendencies. Ysaÿe is included for his often misunderstood elegance, Bacewicz for her devilish energy. And Prokofiev's Solo Sonata was picked for being an underrated little gem of the solo violin repertoire. Finally, in his Sonata for solo violin, Bartók writes in a musical language that at once pays tribute to J.S. Bach and his own deep affinity for the folk tradition. I am drawn to this world of musical connections: the counterpoint and complex structures of Bach's solo writing meets the rhythms and sense of movement found in Magyar folk music. It is one of those pieces that lives with you, possesses you."

Saluste-Bridoux was a prize winner in the inaugural Young Classical Artists Trust (London) and Concert Artists Guild (New York) 2021 International Auditions. Other recent career highlights include appearances at Wigmore Hall, a BBC Prom with the dynamic 12 Ensemble, and a performance of the Franck Piano Quintet at the Gstaadt Festival with Alina Ibragimova, Lawrence Power, Sol Gabetta and Bertrand Chamayou.

Charlotte plays a wide variety of repertoire, including rarely heard solo concertos by Panufnik, Vasks and Joachim, the last of which she has performed, alongside Bernstein's Serenade, with the Concerto Budapest Orchestra conducted by András Keller.- Sleeve Notes

Strands of western culture and psychology are closely woven through the history of the instrumental sonata. Their development over time helped transform it from a broad category of ensemble music, freely invented without formal constraints, to a particular genre concerned with exploring and expressing the solo self and its relationship to an accompanying other. The sonata, born as a catch-all term for instrumental works of many kinds, itself gave birth to a form, or at least to a model from which a multitude of formal variations were teased and applied to a movement or movements within a single composition. While works for a melody instrument and keyboard dominate the sonata repertoire, composers also explored the limitless possibilities inherent in the solo sonata, perhaps drawing inspiration from the word’s Italian origin in the verb suonare, ‘to sound’, and certainly from advances in playing techniques made by generations of outstanding individual performers.

Charlotte Saluste-Bridoux’s programme embraces the mix of the rational and the intuitive, of head and heart, in five diverse compositions, each marked with the solo sonata stamp yet strikingly different in style and substance. While sharing the common ground of taxing technical difficulties and virtuoso display, they range from the devotional communion of Biber’s ‘Guardian Angel’ Passacaglia to the intense introspection of the Melodia from Bartók’s Sonata for solo violin and the sense of loss that pervades Bacewicz’s second solo sonata, a post-war work marked by its composer’s reflections on the brutality of totalitarianism and the angst of the atomic age.

The musical antiquarian Charles Burney, writing in the 1770s, noted that ‘of all the violin players of the last century Biber seems to have been the best, and his solos are the most difficult and most fanciful of any music I have seen of the same period’. Little is known of Heinrich Biber’s early life and particularly of his musical training. He was born around fifty miles north of Prague in the small town of Wartenberg, where his father served as gamekeeper to Count Christoph Paul von Liechtenstein-Castelkorn. It appears that the count introduced young Heinrich to his music-loving relation, Karl II Liechtenstein-Castelkorn, Prince- Bishop of Olomouc. Before becoming a member of the bishop’s illustrious musical establishment at Kromev rv ízv Castle in Moravia, Biber may have served Prince von Eggenberg at his residence in Graz and elsewhere in Styria. He was a member of Prince-Bishop Karl’s instrumental ensemble by 1668, and, two years later, was reprimanded for leaving Kromev rv ízv without permission. During the winter of 1670, Biber was listed among musicians serving the court of Maximilian Gandolph von Kuenburg, Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg. He rose from the ranks to become Salzburg court composer, vice-Kapellmeister and, in 1684, court Kapellmeister and dean of the cathedral choir school. He performed several of his solo sonatas for Emperor Leopold I in 1677 and was ennobled by him thirteen years later.

Biber’s skills as a performer were celebrated during his lifetime, while his instrumental compositions proved sufficiently popular to merit the publication of several collections of sonatas and other pieces. Although the title-page is missing from the original manuscript of his ‘Rosary’ or ‘Mystery Sonatas’, its contents are clearly related to meditations from the Christian Rosary devotion. The sacred connection is made plain by etchings associated with the mysteries of the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary, probably cut from a devotional book, that preface each of the fifteen sonatas. It is possible that the sonatas were also associated with the Feast of the Guardian Angels, a localised memorial rite added to the Roman Catholic calendar by papal decree in the early 1600s.

Biber crowned his sequence of rosary sonatas with a Passacaglia in G minor for unaccompanied violin, illustrated in its manuscript source by an etching of a child being led by its guardian angel. The work’s first four notes follow the traditional bass pattern of the Italian passacaglia; they also, as the musicologist Peter Holman has suggested, echo the opening line of ‘Einen Engel Gott mir geben’, a German hymn to the Guardian Angel current during Biber’s lifetime. Its counterpoint, built above the repeated ground bass, invites meditation on life’s labyrinthine journey and Christ’s promise to his followers of eternal life.

Béla Bartók’s career-long fascination with folk music and periods of field research as an ethnomusicologist left impressions on his musical language, sometimes clear, sometimes less so. The Sonata for Solo Violin, commissioned by Yehudi Menuhin and first performed by him at Carnegie Hall, New York, in November 1944, rises from a chord that evokes the opening of the Chaconne from Bach’s Partita in D minor for solo violin. Bartók soon dispels the allusion with a succession of fragmentary melodic ideas often flavoured by intervals characteristic of Hungarian folk music, which he gathers and organises into a loose yet definite sonata form, complete with exposition, development and recapitulation. The movement’s tempo di ciaccona marking refers no doubt to the rhythm of its first subject, deliberately modelled after that of Bach’s Chaconne.

Shades of Bach surface again in the second and third movements, ruled by Bartók’s close preparatory study of the German composer’s Sonata in G minor BWV 1001. Bartók, like Bach in his G-minor Sonata, sets the violinist the task of performing (or at least implying) a four-voice fugue in the work’s second movement, albeit far from strict in nature and interlaced with contrasting episodes, and presents its haunting slow movement, again like Bach, in B flat. The Melodia, cast in ternary form and based on material from the first movement’s second subject, includes a muted central section hallmarked by the spectral trills and soaring harmonics of Bartók’s so-called night music style. The finale, peppered at first with optional microtones, finds relief from its initially relentless rhythmic thrust in two contrasting sections informed by folk-music influences, the first built from a pentatonic scale, the second forged from a lyrical diatonic melody that grows wilder as the movement hastens to its conclusion.

Prokofiev’s Sonata for solo violin in D major Op.115 presents the stylised gestures of Baroque dance and early classical chamber music in modern melodic fashion. The work was written in 1947 in response to a commission from the Soviet Committee on Arts Affairs for a work suitable for talented young players. Prokofiev responded with a three-movement sonata that could be performed either by solo violin or by violins in unison. It seems likely that both Committee and composer had in mind Kreisler’s pastiche pieces, elegant and refined in style, free from excessive technical demands. The Sonata’s opening movement unfolds within sonata form, complete with a swaggering first subject and sonorous coda. Prokofiev’s second movement grows from a wistful theme with five variations; the work’s mazurka-like finale, meanwhile, flecked with double stops, is propelled by an apparently boundless energy.

Born and raised in the industrial city of Łódź, then part of the Russian- controlled Kingdom of Poland, Grażyna Bacewicz studied piano and violin with her father, a choral conductor and composer originally from Lithuania. Soon after the creation of the Second Polish Republic at the end of the First World War, she enrolled at the fine local music school run by the pianist and influential teacher Helena Kijeńska-Dobkiewiczowa and continued her training at the Warsaw Conservatory, taking lessons in composition from Kazimierz Sikorski, violin from Józef Jarzębski and piano from Józef Turczyński. Bacewicz’s progress as composer and violinist was accelerated by periods of study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger and the violinist André Touret and Carl Flesch.

On her return to Warsaw, Bacewicz accepted the conductor Grzegorz Fitelberg’s invitation to join the first violins of the newly formed Polish Radio Orchestra. She took advantage of her two years with the orchestra to deepen her knowledge of instrumentation. Her solo career flourished in the late 1930s at home and abroad, propelled by the success of a fine duo partnership with her pianist brother, Kiejstut, and also by an acclaimed appearance as soloist with the Polish Radio Orchestra in her own First Violin Concerto. She continued to perform after the Second World War until the mid-1950s, when she decided to devote her time exclusively to composition. Bacewicz’s first sonata for solo violin was written during her student years in Warsaw and later discarded as an immature work. She completed her official Solo Sonata No.1 in 1941 and gave its first performance at a concert in Warsaw organised by the Polish underground during the Nazi occupation. Her Solo Sonata No.2, written in 1958, combines elements of the elegant neo-classicism of its predecessor with a hard-hitting, more acerbic style. The short piece, in three contrasting movements played almost without a break, develops from an introspective exploration of a sustained unison and its neighbouring notes.

Bacewicz repeatedly builds and dissipates tension in the opening Adagio, contrasting formal patterns of held notes and dance-like figures with wilder improvisatory outbursts and a yearning central melody that fragments as it gradually unfolds. The sonata’s second Adagio, prefaced by the disconcerting energy of harsh pizzicato chords and an extended silence, suggests the contemplation of a great truth about existence, something beyond the restricting limits of words. After such an interlude, only silence or subversion will suffice; Bacewicz delivers both, allowing the Adagio to resolve into peace before unleashing the moto perpetuo whirlwind of her sonata’s finale, a headlong Presto dash of double-stopped scale figures and unsettling glissandos.

‘All the Ysaÿes played the fiddle as a matter of course,’ wrote Eugène Ysaÿe’s son, ‘and as a matter of course [my father] would naturally follow the family tradition.' How could he escape it? His destiny was already cast – straight from the atavistic crucible.’ A heavy paternal fist, frequently raised and unleashed, forced young Eugène to practise scales and arpeggios. Strict discipline also ruled the boy’s studies with his father. ‘He was very free with his hands,’ Ysaÿe recalled in later years, ‘and it wasn’t without provoking in me a sullen tendency towards rebellion and even a certain distaste for the violin that he clouted me so hard when I wanted to go and play with the other children.’ The father also passed to his son what Ysaÿe described as the gift of being able to ‘speak through the violin’, a facility subsequently buttressed by technical and musical lessons learned from Henryk Wieniawski in Brussels and Henri Vieuxtemps in Paris.

From the 1880s to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Ysaÿe established his place among the great touring virtuosos, ‘an ornament to the world of violinists’ as the Austrian journalist and critic Franz Farga observed. Ysaÿe’s duo partnership with the French pianist Raoul Pugno introduced audiences to recital programmes comprising nothing other than sonatas, an innovation soon universally copied. His compositions ventured far beyond the conventional realm of encore pieces to display a genuine breadth of invention, especially so in the Six Sonatas for solo violin Op.27. Ysaÿe, inspired by hearing Joseph Szigeti perform Bach’s Violin Sonata No.1 in G minor BWV 1001, drafted his sonatas in the summer of 1923. He notated their thematic ideas and formal outlines within the span of twenty four hours, paying homage to the past by evoking the spirit of the Baroque dance suite and inventing passages that sound as if they might have been composed by Bach himself.

The Fourth Sonata is dedicated to the Austrian virtuoso Fritz Kreisler, whose own encore pieces in the Baroque and classical style proved his considerable skill as a pasticheur. Ysaÿe appears to suggest that anything Kreisler could do, he could do better and advertised the fact in the work’s Allemande and Sarabande, quintessential Baroque dance forms. Each of the sonata’s three movements is based on a four-note theme, stated as a rising scale immediately following the Allemanda’s slow introduction; presented in reverse as pizzicato and bowed figures in the Sarabande; and recalled again in descending order in the Finale. The latter’s barrage of scampering semiquavers, delivered in 5/4 time, is offset by a central section in triple time that belongs more to the 1720s than the 1920s.

[Andrew Stewart]

- Press Reviews

- Delivery & Returns

If you order an electronic download, your download will appear within your ‘My Account’ area when you log in to the Champs Hill Records website.

If you order a physical CD, this will be dispatched to you within 2-5 days by Royal Mail First Class delivery, free worldwide.

(We are happy to accept returns of physical CDs, if the product is returned as delivered within 14 days).

If you have any questions about delivery or would like to notify us of a return, please get in touch with us here.