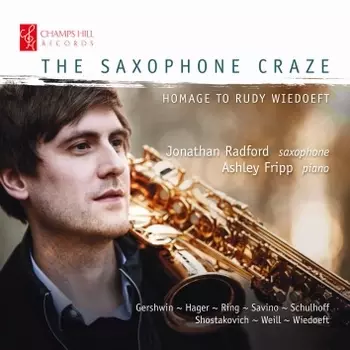

The Saxophone Craze - Homage to Rudy Wiedoeft

CHRCD166-E

- About

- For his debut recording, Jonathan Radford pays homage to the American saxophonist Rudy Wiedoeft, a hugely virtuosic musician who arguably secured the future of the saxophone in the 1920s and 30s.Together with pianist Ashley Fripp, saxophonist Jonathan Radford brings together several Wiedoeft compositions, pairing them with works that were written for or included saxophone in their original orchestrations. The music featured on this album has helped shape the instrument into what it has become today: "It is my hope that this album will pay homage to an important icon from the Roaring Twenties, whilst celebrating the diverse nature of the saxophone across genres.” [Jonathan Radford]Saxophonist Jonathan Radford is passionate about showcasing the instrument's versatility across the classical and contemporary repertoire. He studied at Chetham’s School of Music (UK), before entering the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris (CNSM) in the class of Claude Delangle. He was the 2018 Mills William Junior Fellow at the Royal College of Music, studying with Kyle Horch, and his doctoral studies at the Royal College of Music entered on researching American saxophonist Rudy Wiedoeft.Jonathan is an international prize-winner, with notable awards including Commonwealth Musician Of The Year and Gold Medallist in the Royal Overseas League Competition (UK, 2018), SaxOpen International Competition (France, 2015) and Concordo Internazionale de Musica Marco (Italy, 2013). Performance highlights include recitals at Wigmore Hall, Southbank Centre, Bridgewater Hall (Manchester), Seoul Arts Center (South Korea), Grieg Hall (Bergen), and Philharmonie de Paris.

- Sleeve Notes

A collective desire for good news swept through Europe and the United States in the aftermath of the First World War. Those too young to serve in the military and those thankful to have survived the carnage of modern warfare wanted pleasure, not pain, a point understood by the entertainment industry. It was time to open new cinemas and dance halls, sell gramophones and records, lift spirits with the diverting sights and sounds of Broadway shows and jazz. The twenties became the ‘era of big business’, a time when fortunes were made and stars were born. One of those stars, who made and lost a fortune, was once a household name, now little more than a footnote in specialist surveys of the period’s music. Rudy Wiedoeft suffered the fate of so many musical pioneers and evangelists, preparing the way for others before falling into obscurity. He was among the first, perhaps the first, to establish the saxophone as something more than a toy-shop novelty, only a few steps up in the evolutionary tree from the kazoo or swannee whistle.

Wiedoeft’s jaw-dropping technical skills and legendary devotion to practice kept his name alive among the global community of sax players. Yet it was the joie de vivre and appeal of his many recordings and compositions that caught the public imagination a century ago. His first recording of Saxophobia, Wiedoeft’s signature piece, sparked a saxophone craze that swept America within months of the disc’s release in 1920. A contemporary advertisement depicts Wiedoeft holding his trademark gold-plated C-melody saxophone while towering over a line of high- kicking chorus girls. ‘Hear Him!’, the copywriter commands. The ad falls short when it comes to the correct spelling of the artist’s name, but is in no doubt that ‘Rudy Weidoeft [sic]’ is the ‘World’s Greatest Saxophone Artist’. Others knew him as ‘The Kreisler of the Saxophone’, a neat comparison for a musician who showed prodigious talent as a child violinist. Young Rudy’s fiddle-playing days were ended when he broke his bowing arm at the age of ten in a cycling accident; he took up clarinet soon after, practised hard and became a professional player long before he left school.

Rudolph Cornelius Wiedoeft was born in Detroit on 3 January 1893. His family came to Michigan from Germany in the mid-1800s, drawn by the recently established state’s campaign to attract agricultural workers from Germany’s kingdoms and principalities with promises of a better life and prosperity in a young country. Brewers from Bavaria were among those who made their way to Detroit, a city noted for its grand avenues and elegant public buildings, already home to French and Irish settlers. Rudy formed a band with his three older brothers, with Herb on trumpet, Adolph or Al doubling on trombone and drums, and Gerhardt or Guy doubling on tuba and double bass. The Wiedoefts profited from Detroit’s hospitality business, thanks not least to little Rudy’s turns in the solo spotlight; following their move to Los Angeles in 1903, the Wiedoeft Family Orchestra, now with their father on violin and sister on piano, was in demand on the hotel circuit.

Wiedoeft added saxophone to his portfolio of instruments around 1908. Years later he recalled spotting one protruding from a green bag in a pawnbroker’s window. ‘I thought there might be big money in the novelty,’ he added. ‘This revolutionary move on my part was not greeted with favour by friends, relations and colleagues.’ Despite hours of practice in the wood-shed, the badly made pawnshop sax proved beyond redemption; Wiedoeft sold it and put the money towards buying a superior saxophone which, in lieu of specialist teaching methods for the instrument, he taught himself to play with help from tutors conceived for the oboe. He continued to build his sax skills after moving to San Francisco in 1913 to become first clarinettist with Porter’s Catalina Island Band, among the attractions used to draw visitors to the burgeoning tourist resort in the Gulf of Santa Catalina, and launched his career as a saxophonist the following year.

Wiedoeft, aware that US audiences regarded saxophone as little more than a child’s toy, recognised the market potential open to the first musician who could demonstrate the instrument’s virtuosity. At the end of 1916 he crossed the United States to find work on Broadway and made his breakthrough in February 1917 at the Morosco Theater in New York City. Wiedoeft graced the show’s four- month run of the musical Canary Cottage with his pulsating roulades and musical ad libs. The future Mrs Wiedoeft, Mary Murphy, a hot-tempered member of the Canary Cottage chorus line, soon joined the musician’s many new admirers. ‘Rudy’s obligatos ... were so thrilling,’ noted one critic, ‘that he took more bows from the pit than the singer from the stage.’

Thomas Edison was also impressed by Wiedoeft, sufficiently so for the near-deaf inventor to invite him to record for the Edison label. Rudy cut his first disc, Canary Cottage One-Step, with the Frisco ‘Jass’ Band in May 1917, and recorded five more pieces for Edison by mid-September, including his solo debut disc, Valse ‘Erica’. In answer to his country’s call, he enlisted in the Marine Corps and ended his short military service in 1918 as a member of the Marine Band in Washington, D.C. While Saxophobia, the work that made his name, dates from the war’s last year, it looks forward to a peace filled with boundless jollity. Rudy Wiedoeft was a phenomenal player and smart self-publicist. He was the first saxophonist to broadcast on a US radio station, indeed one of the first American musicians ever to broadcast a concert, and a box-office draw at America’s grand

picture houses, home to musical variety as well as the movies. He was also a pioneer in matters of saxophone technique, inventor of so-called slap tonguing, master of articulation and purveyor of flawless fingering at the fastest tempos. His recordings unleashed a wave of enthusiasm for saxophone and inspired countless kids to take up the instrument, at times causing demand to outstrip the supply of new saxophones. Wiedoeft’s sliding legato style left its mark on the young Bing Crosby, who freely acknowledged the saxophonist’s influence on his own smooth, crooning vocal technique.

Practice and patience were among the virtues outlined in 1927 by Wiedoeft in his short guide to The Saxophone – with hints on how to play it. His ‘helpful hints’ were signed with a flourish beneath ‘Saxotively yours’, typical of a larger- than-life character who appeared to have stepped out of a Damon Runyon story. He and his wife lived – and often brawled – in New York, in an apartment at 145 W. 45th Street. Their drink-fuelled parties became the convivial front for Wiedoeft’s alcoholism, which gradually affected his playing; his popularity, meanwhile, fell from its peak in the mid-1920s and was further undermined in the early thirties by the Great Depression. In 1926 Wiedoeft travelled to London with the concert pianist Oscar Levant, a noted early interpreter of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. The duo performed at the Prince’s Hotel on Jermyn Street during the summer season, while Levant gave a private performance of Rhapsody in Blue for the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII.

Towards the end of the decade Wiedoeft’s blend of ragtime and vaudeville repertoire was eclipsed by new trends in popular music and jazz, including those brought to the Brunswick label by Bing Crosby, Hoagy Carmichael and the Dorsey Brothers. The Wiedoefts moved to Paris, where Rudy and his music were still in demand, but soon tired of the City of Lights. They returned to the United States, where the death of one of Wiedoeft’s brothers and a disastrous investment in a gold mine in California’s Death Valley pushed him to become increasingly dependent on alcohol and reliant on credit. The combination of falling income and rising domestic pressure finally exploded in March 1937, when Mary Wiedoeft almost killed her husband with a meat knife; he chose not to press charges and she later explained that it was simply a kitchen accident. The couple were reconciled and lived together at their Long Island home until Wiedoeft’s death from cirrhosis on 18 February 1940.

Jonathan Radford decided to learn more about Wiedoeft when he heard a few of his recordings. He was amazed by the saxophonist’s technical command and the quality of his sound; and he was seduced likewise by the charm of Wiedoeft’s compositions, written for a young instrument that lacked solid technical foundations. ‘There are still things about his articulation and virtuosic technique that nobody has been able to come even close to,’ notes Radford. ‘Rudy Wiedoeft grew up in a family who played many different instruments. His saxophone playing could easily have been inspired by the violin; he definitely applied his sense of string legato and articulation to saxophone.’

The Saxophone Craze looks back to the Roaring Twenties. This album represents a wish to see a return of the decade’s best attributes: its optimism and sense of fun. Wiedoeft was in tune with the age that mass-produced everything from bicycles and cars to valve radios and gramophones, and raised living standards across Europe and the United States. Between 1917 and 1930 he made over 300 78rpm recordings for, among others, the Edison, Aeolian-Vocalion, Emerson, Victor, Columbia, OKeh and Brunswick labels. Some were pressed, supposedly under licence, in the Soviet Union, extending his reach to the world’s first socialist state.

In addition to trademark vaudeville tunes, Wiedoeft composed pieces that sound at ease in the classical concert hall. Dans l’orient, for instance, pays homage to the fashion for all things exotic, present throughout the twenties in everything from the fairground Palais de danses orientales to the orientalist designs of Art Deco cinemas, while the Danse hongroise connects with an older trope in classical music, familiar at least since Haydn’s time. Waltz-Llewellyn and Valse Marilyn, miniature showpieces created to fit one side of a 78rpm disc, are both blessed with charm comparable to that of Fritz Kreisler’s violin encore pieces. ‘Before Wiedoeft began his career, the saxophone was considered to be a novelty item or something you might see in a military band,’ observes Jonathan Radford. ‘It was certainly absent from the classical concert world. Wiedoeft transformed perceptions of what the saxophone was and what it could do. He was influential in the development of different genres for the instrument, even though he was neither a classical nor a jazz player; in fact, he’s very difficult to pigeonhole, which is why I think he inspired musicians from so many backgrounds. It’s interesting that he and Rachmaninov played in the same concert in the twenties; perhaps Wiedoeft inspired Rachmaninov to include saxophone in his Symphonic Dances.’

This album invites listeners to consider Wiedoeft’s legacy and influence on others, whether direct or indirect. Saxophone, absent from the earliest jazz bands, became the genre’s pre-eminent instrument during the 1920s, in part thanks to the Wiedoeft-inspired sax craze, in part by Wiedoeft’s younger contemporaries Sidney Bechet and Frankie Trumbauer. Jazz offered a rich creative refuge to Erwin Schulhoff throughout the Roaring Twenties and beyond. The Prague-born composer and pianist’s frontline experiences in the Austrian army from 1914 to 1918 informed his pacifism and socialism, while his post-war encounter with the painter George Grosz, among Germany’s first collectors of American jazz recordings, opened his ears to music filled with vitality and joy. Schulhoff interrupted work on his jazz oratorio H.M.S. Royal Oak to compose the Hot-Sonate. The latter, written in 1930, represents the saxophone’s apotheosis as a classical concert instrument, perhaps the noble alter ego of the sexualised saxophone that Schulhoff had described in a colourful article published in 1925. Its four movements marry the rhythmic riffs and roulades of jazz to the formal logic of a classical sonata. Kurt Weill, like Schulhoff, received anti-Semitic abuse from Hitler’s Nazis, while his music was officially banned by Germany’s fascists; unlike Schulhoff, who died of tuberculosis at the Wülzburg concentration camp during the Second World War, Weill escaped the Nazi Reich in 1933 to find refuge in the United States. Jonathan Radford and Ashley Fripp’s selection of music from Weill and Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera recalls one of the Weimar Republic’s cultural triumphs. First staged in Berlin in 1928, the work became an international hit and set the foundations for Weill’s integration of classical and jazz styles within the same composition.

The saxophone became a glamourous guest in classical orchestras during the 1920s, heard in works such as Milhaud’s La création du monde (1922–23), Ferde Grofé’s orchestration of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (1924), Kodály’s folk opera Háry János (1926) and Gershwin’s An American in Paris (1928). Shostakovich included saxophone parts in his early film scores for the silent and sound cinema, the ballet The Golden Age (1930) and his two Suites for Jazz Orchestra (1931 & 1938). The Suite for Variety Orchestra (written after 1956) was misidentified for many years as the second of the Jazz Suites until a piano score of the latter surfaced in 1999. Its Waltz No.2 reached a wide audience after Stanley Kubrick used it as the title theme and music for the closing credits in his final film, Eyes Wide Shut.

The Soviet regime banned jazz during the 1920s and 1930s, branding the genre and the saxophone as symbols of bourgeois decadence. Saxophones continued to be produced at the old Zimmermann factories in Leningrad and Moscow, which had been nationalised following the October Revolution in 1917. Zimmermann’s copies of American Conn instruments were stamped with the hammer and sickle on their bells. The egalitarian saxophone, easy to play yet truly hard to master, was authorised for use in military bands and concert orchestras, while performing its subversive part in clandestine jazz gigs. The instrument’s versatility and staying power, proof against attacks by totalitarian regimes and puritanical condemnations of the ‘Devil’s Horn’, owes a considerable debt to Rudy Wiedoeft, the man who turned the saxophone from toy into a serious musical champion.

[Andrew Stewart]

- Press Reviews

- Delivery & Returns

If you order an electronic download, your download will appear within your ‘My Account’ area when you log in to the Champs Hill Records website.

If you order a physical CD, this will be dispatched to you within 2-5 days by Royal Mail First Class delivery, free worldwide.

(We are happy to accept returns of physical CDs, if the product is returned as delivered within 14 days).

If you have any questions about delivery or would like to notify us of a return, please get in touch with us here.